![]() 01443 412248

01443 412248

![]() 01443 412248

01443 412248

History

at Llancaiach Fawr

Llancaiach Fawr is situated in South East Wales in the small valley of the Nant Caiach, a stream from which it takes its name. The site has been occupied for almost 4,000years. We believe that there was probably an earlier dwelling on the site, either underneath the present house or possibly incorporated within the eastern end of the building.

It was previously thought that Llancaiach Fawr Manor predates the Acts of Union between Wales and England of 1536 and was mentioned in John Leland’s Itinerary of 1537. However, tree ring dating carried out by the Time Team suggests a felling date for the roof timbers ( those which have sufficient sap wood left to test) of between 1548-1565, later than was originally thought. Leland’s Itinerary could therefore reference an earlier house on the site or a house belonging to the Prichard’s in the parish of Gelligaer- the parish formerly included Dowlais near Merthyr Tydfil, which is where this branch of the family came from originally as so Leland may be referring to their house in Dowlais.

The search for the origins of the house continue and the presence of medieval ridge and furrow plough marks shows long standing agricultural use of the land surrounding the present manor. The construction of a huge palisaded enclosure in the adjacent field has been dated to 1494 BCE through carbon dating- the ideal conditions of trackways, water and flat ground have made this small area a tempting location to live for millennia.

The Manor House was constructed for the Prichard (ap Richard) family when ‘gentle birth’ was no guarantee of security and was built to be defended. The walls are 4’ (1.2 metres) thick and access between floors was by stairs inside the walls. The entire house could be divided in two if attacked and only those in the secure east wing had access to the latrine (toilet) tower. Sturdy floors and small ground floor windows bear further testimony to the turbulence of 16th Century Glamorgan.

As time went on the Prichard family began a series of improvements to their home to demonstrate their growing affluence and prosperity. In 1628 the Grand Staircase was added and two rooms were beautifully panelled and several of the intramural staircases were sealed off. At the same time a formal garden was laid out.

The existence of passages and stairways walled up over the years leads to the interesting situation where there are more windows visible from outside Llancaiach Fawr Manor than can be seen from the inside.

The earliest reference might be in Leland’s ‘Itinerary’. Visiting Glamorgan in the wake of the Acts of Union from 1536, John Leland noted that there were but ‘three gentlemen of fame’ in Senghenydd, two of them being Edward Lewis and David ap Richard. He describes David Richarde, dwelling at ‘Kellhle Gare’ in ‘Huhkaihac’. ‘Kelthle Gare’ is from another reference and is the parish we now call Gelligaer, and it would seem reasonable to assume that ‘Huhkaihac’ is an attempt to transliterate ‘Uwch Caiach’, ‘The House’ above the (river) Caiach.

The earliest reference might be in Leland’s ‘Itinerary’. Visiting Glamorgan in the wake of the Acts of Union from 1536, John Leland noted that there were but ‘three gentlemen of fame’ in Senghenydd, two of them being Edward Lewis and David ap Richard. He describes David Richarde, dwelling at ‘Kellhle Gare’ in ‘Huhkaihac’. ‘Kelthle Gare’ is from another reference and is the parish we now call Gelligaer, and it would seem reasonable to assume that ‘Huhkaihac’ is an attempt to transliterate ‘Uwch Caiach’, ‘The House’ above the (river) Caiach.

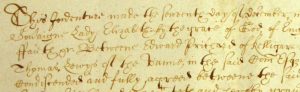

The spelling ‘gare’ also indicates that the local pronunciation today has not changed substantially in four hundred years. The next reference we can find is in Edward Prichard’s marriage settlement of 1578, which mentions ‘a capital mansion house called Glankayach’, Here ‘Glankayach’ means ‘(the house) on the bank of the (river) Caiach’. This name is used throughout the following century, usually in the form ‘Glancayach’ but seems to have been changed to ‘Llancaeach’ sometime in the eighteenth century and later still to its modern spelling.

A series of investigations during the first stages of restoration of Llancaiach Fawr by the Welsh School of Architecture uncovered a number of highly unusual features as well as confirming that the house was much older than originally thought before any in depth studies were undertaken. It became clear that the house had been constructed with the security of its occupants as the main objective.

This accounts for the extraordinary number of steep intra-mural stairs in the building. Even today the house suggests a defensive enclosure, with its massive walls, small ground floor windows and forbidding air. Other evidence shows there was intense rivalry at the time and in later generations – between the Lewis branch of the family at the Van and the Prichard branch at Llancaiach Fawr. It may be that the house was so constructed as protection against offensive action or possible reprisals.

It is the survival of the evidence for this Tudor defensive arrangement that makes Llancaiach Fawr unique.

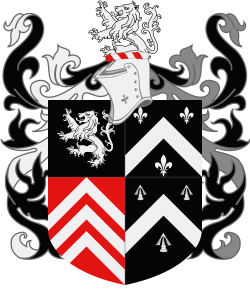

The Prichards were proud of their heritage, boasted about their genealogy, and pointed to their descent from Ifor Bach. Ifor Bach, described by Gerald of Wales as ‘a man of short stature but good courage’ was one of the common ancestors shared by the Prichards and the Lewis’ of the Van (and later St. Fagans).

The Prichards were proud of their heritage, boasted about their genealogy, and pointed to their descent from Ifor Bach. Ifor Bach, described by Gerald of Wales as ‘a man of short stature but good courage’ was one of the common ancestors shared by the Prichards and the Lewis’ of the Van (and later St. Fagans).

At some point possibly after an incident involving the murder of a kinsman of Edward Lewis apparently by a servant of Edward Prichard (senior), the Lewis and Prichard sides of the family appear to have fallen out with each other leading to brawls – on one occasion in Gelligaer Church! There were also court cases involving Edward and his two sons and members of the Lewis and Williams of Gelligaer families. A total of eleven cases were brought before the Star Chamber, concerning Edward Prichard and his son David. These offences included:

“Brawling in Gelligaer Church”, “an assault at Merthyr” and “resistance to arrest”

“Assaults at Cardiff and abuse at the sessions there”;

“Assault by Edmund Lewis in revenge against David Prichard for attempts to put down an unlawful market on a mountain, called Ffait-y-Waun” (Ffair-y-Waun?)

“Assault and riot at Gelligaer by David Prichard, his brother Thomas and his man, Stephen Rooke”;

“Attack by David Prichard, his brother Thomas and his man Stephen Rooke on the house of Edward William, yeoman, and assault at Gelligaer”

“Bribery of a witness to confess perjury at a former suit”.

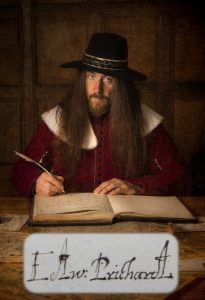

It is not certain exactly when Edward Prichard was born but we believe it to have been fairly early in the 17th century, possibly about 1610. Nor do we know where he was born for it is thought that the Prichard family had more than one house, although it is most likely that his birthplace was Llancaiach Fawr.

It is not certain exactly when Edward Prichard was born but we believe it to have been fairly early in the 17th century, possibly about 1610. Nor do we know where he was born for it is thought that the Prichard family had more than one house, although it is most likely that his birthplace was Llancaiach Fawr.

Unfortunately little is known of his early life. He really came to prominence during the Civil War period. By this time he would have already married Mary Mansel (possibly in the 1630’s), and his children probably would have been born – his two sons having “died young”. Much of this is supposition, as thus far few records for this period of his life have come to light. It may be just that he behaved himself, unlike many of his forebears who spent a lot of their time in court and their activities have therefore been recorded!

What is certain is that he held the position of Sheriff of Glamorgan in 1638 and was appointed a Justice of the Peace in 1640, a post he held throughout the Civil War until his death in 1655.

Edward Prichard supported the Royalist cause until the second half of 1645, when, like most of the Welsh gentry, he changed his allegiance to the Parliamentarian side. It was late in this year that he was appointed Governor of Cardiff Castle. In February of 1646 he staunchly held the Castle for the Parliamentarians against a siege headed by Edward Carne. He was also commended “for his constancy in that affray” after the battle of St Fagans (1648), by Colonel Horton, the Parliamentary victor.

It is known that Edward Prichard had also been appointed as one of the County Commissioners for the administration of the Act of Propagation (of the Gospel in Wales), and that he was therefore able to examine clergymen for “delinquency, malignancy and non-residence”. He is known to have been a Baptist, and a member of a group that met at Graig-yr-Allt, Eglwysilan. He is thought to have had Puritan sympathies.

Sadly at the end of 1649 that his wife died. In the October, just hours before her death, she wrote a letter to her brother, asking that he should make arrangements for the upbringing of their two daughters, there being no gentlewomen locally who could attend to their education. The loss of his wife and likely separation from his daughters must have been a bitter blow, for he never married again. He survived his wife by only six years.

Charles Stuart was born in Dunfermline Castle on the 19th November 1600, the younger son of James 6th of Scotland who succeeded to the English throne and became James 1st of England in 1603.

Charles Stuart was born in Dunfermline Castle on the 19th November 1600, the younger son of James 6th of Scotland who succeeded to the English throne and became James 1st of England in 1603.

Unlike his elder brother Henry, Charles was a sickly child, suffering from weak joints in his legs and a speech impediment, which was possibly the cause for his shyness and reserve. He was determined to overcome these difficulties and eventually became a skilful horseman and accomplished in many sports such as tennis, although this determination may have led to his stubbornness in later life.

He remained in Scotland until August 1604, when he was brought to England to be cared for by Sir Robert and Lady Cary until he was eleven years old. It was customary for children of noble birth to spend their early years with families other than their own. He was treated very much as the baby of the Royal family and appears to have been his mother’s favourite, but nonetheless he received a good education and was deeply religious. He also developed a love of the arts and music.

Charles became heir to the throne on the death of his brother Henry, probably of typhoid fever, in November 1612. He was therefore groomed for kingship and succeeded to the Throne on the death of his father in March 1625.

He was married later in this same year to the fourteen-year-old French Catholic princess, Henrietta Maria, and although they were not happy at first, they later became devoted to one another. They had eight children, three of whom died young.

Charles was not a good politician, and was greatly influenced in the beginning of his reign by his friend, George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, whose disastrous advice regarding foreign policy, and Charles’ demands for money to fight unwise wars, caused the initial rift between the King and his Parliament. Buckingham was assassinated in August 1628, but by then much damage had been done and in 1629 Parliament was dissolved and was not called again for the following eleven years, the King choosing to rule without their advice.

During his years of rule without Parliament, Charles seems to have lost touch with the opinions and concerns of his subjects in both political and religious matters. Opposition to him grew, particularly among the Puritans and he showed little skill in diplomacy as he tried to regain his authority, for he still treated Parliament with contempt.

Discontent continued to grow throughout the country until August 22nd 1642 when Charles made a formal call to arms against Parliament, and raised his standard at Nottingham. A blustery wind blew it down again and many saw this as a bad omen for the future. The first pitched battle of the Civil War was fought at Edgehill, but proved to be indecisive. As London was held by Parliament, Charles set up his Court at Oxford.

Discontent continued to grow throughout the country until August 22nd 1642 when Charles made a formal call to arms against Parliament, and raised his standard at Nottingham. A blustery wind blew it down again and many saw this as a bad omen for the future. The first pitched battle of the Civil War was fought at Edgehill, but proved to be indecisive. As London was held by Parliament, Charles set up his Court at Oxford.

Nor was the King a good military tactician. Many battles and skirmishes were fought but in the main they were inconclusive until July 1644 when the battle of Marston Moor proved decisive with the defeat of the king’s army. Although his forces were greatly weakened and funds were short, the King chose to fight on even though the Parliamentary side offered conciliation.

In June 1645, at Naseby, Charles’ real hopes were finally destroyed, his army being completely routed and divided. Documents were found showing that he was willing to seek help from the French and Irish, making concessions to the Catholics that he had refused to the Presbyterians, thus showing that he could not be trusted. Even then, his stubborn nature would not allow him to yield.

He made for Wales and the West, in hopes of gathering forces again. It was at this time that he came to Llancaiach Fawr and had discussions with Edward Prichard, but these were plainly unsuccessful because soon afterward Prichard, like many other members of the Welsh gentry, declared for Parliament.

Eventually, Charles made for Scotland in hope that he could come to some agreement that would preserve the Monarchy but his duplicity proved to be too much. He was handed over to the Parliamentarian side and taken prisoner. Although he was treated with respect, he had lost much of his power as King. In his attempts to regain this power he still proved to be entirely untrustworthy in the eyes of many.

He had been imprisoned in Hampton Court, but escaped to the Isle of Wight, only to be taken prisoner once more, this time more closely guarded. All this time the opposition tried to come to terms with him but as there was now discord between the Parliament and the army, Charles tried to play one side off against the other, once more proving his untrustworthy nature. Skirmishes and revolts continued in support of the King, but they were quickly dealt with. This “Second Civil War” proved to be his downfall. Oliver Cromwell and his son-in-law Henry Ireton were to be instrumental in the demand for Charles to be brought to trial.

Charles was brought to London and tried for Treason. Although he made a brave and eloquent defence of his actions, he was nonetheless found guilty and his Death Warrant, signed by fifty-nine men, stated that the King “be put to death by the severing of his head from his body.” He was executed on the scaffold that had been built for the purpose outside Whitehall Palace, on January 30th 1649.

When the Rhymney Valley Council bought Llancaiach Fawr Manor, a thorough scientific survey of the garden was carried out in order to discover whether any evidence of the design of the original garden still remained. As the area had become a working farm over the years, any visible signs had long since disappeared but fortunately, beneath the ground there remained sufficient outlines and pollen grains to give us some idea of how parts of the garden may have looked and what was planted there. The Council therefore originally planted the garden according to this evidence.

When the Rhymney Valley Council bought Llancaiach Fawr Manor, a thorough scientific survey of the garden was carried out in order to discover whether any evidence of the design of the original garden still remained. As the area had become a working farm over the years, any visible signs had long since disappeared but fortunately, beneath the ground there remained sufficient outlines and pollen grains to give us some idea of how parts of the garden may have looked and what was planted there. The Council therefore originally planted the garden according to this evidence.

However, it was later decided to add certain elements that might have been in any sixteenth or seventeenth century garden such as the Pond, Shady Walk and Knot garden etc. Thanks to the efforts of the “Friends of Llancaiach”, who provided the funds and some physical help alongside our staff, these areas were soon developed, along with the Orchard, Physic, Privy and Vegetable gardens, whilst still retaining the original layout in the Formal area at the front of the Manor.

As much as possible we try to grow the sort of plants that would have been grown in a garden of the period of the Manor. The orchard contains varieties of apples that are now rarely found such as “ Decio”, “Paradise”, and “Catshead” among others. Plants are grown in the Physic garden that would have been used for cures, household use and perfumes etc.

Whilst our gardens are continually developing, we hope that they retain some of the charm of the early gardens and that our visitors might gain a hint of what might have been enjoyed by earlier generations who took such great pleasure and made such good use of this pleasant space.